Something's Fishy in the History of the Great Lakes

By Katie Larson, Alliance for the Great Lakes, [email protected]

To download a printable version of this lesson plan, click on the image

We would greatly appreciate your feedback! Click here to complete a short survey telling us about your experience with this lesson plan.

By Katie Larson, Alliance for the Great Lakes, [email protected]

To download a printable version of this lesson plan, click on the image

We would greatly appreciate your feedback! Click here to complete a short survey telling us about your experience with this lesson plan.

Lesson Overview

Students work in groups to examine a time period’s interaction and influence on the Great Lakes fishery. They categorize the events of the time period, including the arrival and impacts of invasive species during the time period, and then present the information to the class, using discussion and diagrams to synthesize information and come to a historical understanding of the Great Lakes fishery.

Introduction/Teacher Background

The fishery resources of the Great Lakes were long known to native peoples, who used nets, hook and line, spears and other techniques to catch fish for a thousand years before Europeans entered the region. Native peoples in the area included the Odawa, Saulteaux, Potawatomi, and Ojibwe (Chippewa). They hunted fish for subsistence and for trading between tribes and, later, for trade with Europeans. Indigenous people’s diet included species like Whitefish, Lake Trout, Sturgeon, Walleye, Cisco, and Atlantic Salmon, which were plentiful in the Great Lakes.

When Europeans first arrived in the Great Lakes region, they were astounded at the variety of fish in the Great Lakes, encountering giant lake trout and huge schools of yellow perch. Settlers consumed the bountiful fish locally as well as shipping their catch out to major population centers for food. Ancient lake sturgeon were so abundant that, in the early 19th century, they were derided as “trash fish,” burned as fuel, or simply allowed to rot on the shore. It was said that Atlantic salmon were so plentiful in Lake Ontario that they could be removed by hand.

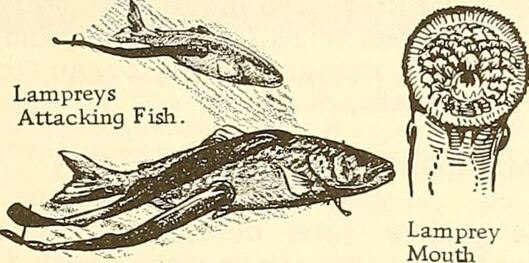

In the mid-19th century, the abundant fisheries became the target of serious overfishing by commercial fishermen and habitat alterations from deforestation. Catches of sturgeon, now commercially valuable, had plummeted. Atlantic salmon had been completely removed from Lake Ontario. States began to try their hand at fish stocking (adding fish to the lakes) with little success. As if the damage wrought by the 19th century wasn’t enough, Great Lakes fish faced a host of new problems: invasive species and industrial pollution. To make up for the decline in native predator fish, state fishery managers began stocking Pacific salmon that ate another invasive species, the alewife. By the mid-20th century, the Great Lakes had fewer native fish than they ever had, and many of the fish that were left were unsafe to eat or embattled in a fight with the sea lamprey. The most abundant fish were artificially stocked and invasive species.

Several 20th century policies have figured into the stabilization of the problems with the Great Lakes fishery, but the Great Lakes fishery is still embattled today. It is unclear if the balance is shifting towards renewal or continued decline. More information about the history and current status of the Great Lakes fishery can be found in the source reference by Brandon C. Schroeder, Dan M. O'Keefe, and Shari L. Dann (2019). See also https://fishingbooker.com/blog/history-of-fishing-on-the-great-lakes-part-1/ and https://fishingbooker.com/blog/history-of-fishing-on-the-great-lakes-part-2/

Target Grade & Subject: Gr. 6-8 Science

Duration: 2 or more 50-minute class periods

Instructional Setting: Classroom

Advance Preparation:

Learning Objectives:

At the end of this lesson, students will be able to:

Michigan Science (or Social Studies) Performance Expectation Addressed:

MS-LS2-4 Construct an argument supported by evidence for how increases in human population and per-captia consumption of natural resources impact Earth's systems.

DCI: Disciplinary Core Ideas

ESS3.C: Human Impacts on Earth Systems

Typically, as human populations and per-capita consumption of natural resources increase, so do the negative impacts on Earth unless the activities and technologies involved are engineered otherwise.

CCC: Cross-Cutting Concepts

Cause and Effect

Cause and effect relationships may be used to predict phenomena in natural or designed systems.

Materials & Quantities Needed per class and per student group

• Great Lakes Fishery Background Information (1 per teacher). See sources.

• Great Lakes Fishery Timeline for Teachers (1 per teacher)

• Great Lakes Fishery Timeline for Student (1 per class, to be cut into separate time period segments)

• Select Creature Cards: native fish could be yellow perch, walleye, lake trout, and whitefish (samples to share with class). Non-native cards could be sea lamprey, alewife, Pacific salmon, and round goby

• Something’s Fishy Journal Page (1 per student)

• Notecards and three different colored pencils/markers for each group of 4 students

Guiding Question(s):

• How have the types and numbers of fish in the Great Lakes changed over time?

• What events or modifications in the Great Lakes region have caused these changes?

5E Model

ENGAGE:

EXPLORE:

Supporting students during exploration: Questions that the teacher could ask to guide the exploration.

EXPLAIN:

ELABORATE:

Supporting students during elaboration: Questions that the teacher could ask to clarify student thinking.

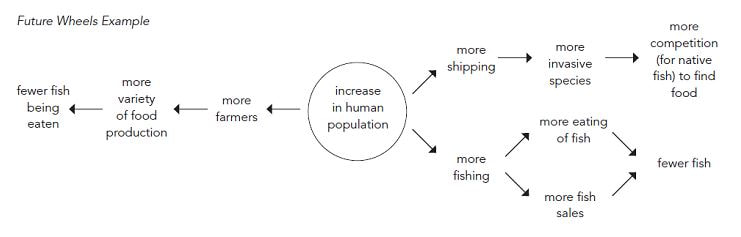

Future Wheels: Have each student choose two changes that happened to the fishery:

An increase in human population means: more fishing, more eating of fish, fewer fish, more fish sales, more shipping more invasive species

Another aspect of a growing human population could be: more farmers--more variety in food types--less fish being eaten

Students work in groups to examine a time period’s interaction and influence on the Great Lakes fishery. They categorize the events of the time period, including the arrival and impacts of invasive species during the time period, and then present the information to the class, using discussion and diagrams to synthesize information and come to a historical understanding of the Great Lakes fishery.

Introduction/Teacher Background

The fishery resources of the Great Lakes were long known to native peoples, who used nets, hook and line, spears and other techniques to catch fish for a thousand years before Europeans entered the region. Native peoples in the area included the Odawa, Saulteaux, Potawatomi, and Ojibwe (Chippewa). They hunted fish for subsistence and for trading between tribes and, later, for trade with Europeans. Indigenous people’s diet included species like Whitefish, Lake Trout, Sturgeon, Walleye, Cisco, and Atlantic Salmon, which were plentiful in the Great Lakes.

When Europeans first arrived in the Great Lakes region, they were astounded at the variety of fish in the Great Lakes, encountering giant lake trout and huge schools of yellow perch. Settlers consumed the bountiful fish locally as well as shipping their catch out to major population centers for food. Ancient lake sturgeon were so abundant that, in the early 19th century, they were derided as “trash fish,” burned as fuel, or simply allowed to rot on the shore. It was said that Atlantic salmon were so plentiful in Lake Ontario that they could be removed by hand.

In the mid-19th century, the abundant fisheries became the target of serious overfishing by commercial fishermen and habitat alterations from deforestation. Catches of sturgeon, now commercially valuable, had plummeted. Atlantic salmon had been completely removed from Lake Ontario. States began to try their hand at fish stocking (adding fish to the lakes) with little success. As if the damage wrought by the 19th century wasn’t enough, Great Lakes fish faced a host of new problems: invasive species and industrial pollution. To make up for the decline in native predator fish, state fishery managers began stocking Pacific salmon that ate another invasive species, the alewife. By the mid-20th century, the Great Lakes had fewer native fish than they ever had, and many of the fish that were left were unsafe to eat or embattled in a fight with the sea lamprey. The most abundant fish were artificially stocked and invasive species.

Several 20th century policies have figured into the stabilization of the problems with the Great Lakes fishery, but the Great Lakes fishery is still embattled today. It is unclear if the balance is shifting towards renewal or continued decline. More information about the history and current status of the Great Lakes fishery can be found in the source reference by Brandon C. Schroeder, Dan M. O'Keefe, and Shari L. Dann (2019). See also https://fishingbooker.com/blog/history-of-fishing-on-the-great-lakes-part-1/ and https://fishingbooker.com/blog/history-of-fishing-on-the-great-lakes-part-2/

Target Grade & Subject: Gr. 6-8 Science

Duration: 2 or more 50-minute class periods

Instructional Setting: Classroom

Advance Preparation:

- Print journal pages for each student.

- Photocopy and cut up the different sections of “fishery time” for the student groups.

- Teacher’s version of the “fishery time” timeline

Learning Objectives:

At the end of this lesson, students will be able to:

- Present historical information to the class.

- Discuss the relative impact of events on the Great Lakes fishery, including the impacts of invasive species.

- Create a diagram that synthesizes historical understanding of the Great Lakes fishery.

Michigan Science (or Social Studies) Performance Expectation Addressed:

MS-LS2-4 Construct an argument supported by evidence for how increases in human population and per-captia consumption of natural resources impact Earth's systems.

DCI: Disciplinary Core Ideas

ESS3.C: Human Impacts on Earth Systems

Typically, as human populations and per-capita consumption of natural resources increase, so do the negative impacts on Earth unless the activities and technologies involved are engineered otherwise.

CCC: Cross-Cutting Concepts

Cause and Effect

Cause and effect relationships may be used to predict phenomena in natural or designed systems.

Materials & Quantities Needed per class and per student group

• Great Lakes Fishery Background Information (1 per teacher). See sources.

• Great Lakes Fishery Timeline for Teachers (1 per teacher)

• Great Lakes Fishery Timeline for Student (1 per class, to be cut into separate time period segments)

• Select Creature Cards: native fish could be yellow perch, walleye, lake trout, and whitefish (samples to share with class). Non-native cards could be sea lamprey, alewife, Pacific salmon, and round goby

• Something’s Fishy Journal Page (1 per student)

• Notecards and three different colored pencils/markers for each group of 4 students

Guiding Question(s):

• How have the types and numbers of fish in the Great Lakes changed over time?

• What events or modifications in the Great Lakes region have caused these changes?

5E Model

ENGAGE:

- Ask students what it means to “eat locally.” Eating “bioregionally” means that individuals eat what is living (bio) within a certain area (region). This can be termed “eating locally.”

- Ask students why “eating locally” would have been more common during historical times. Prior to rapid transportation and refrigeration, people only ate what was from their region. In the Great Lakes area, native people and settlers ate a diet that consisted primarily of Great Lakes fish, meat from animals hunted locally, and fruits and vegetables grown in the region.

- Ask students to create a list of fish they might eat from the Great Lakes. They will probably struggle to create this list. Many of the fish we eat are from the ocean, and fish may not be a big part of students’ diets. Familiarize students with some Great Lakes fish by showing them the yellow perch, walleye, lake trout, and whitefish Creature Cards.

- Discuss the following: Why don’t we eat fish from the Great Lakes as much as we used to? Should people be able to eat what grows and lives in the region?

- How did invasive species get into the Great Lakes? Did this occur “naturally,” or did they arrive in the Great Lakes because of something that people did or built? The Great Lakes could not be reached by big ships until canals were built to enable them to avoid rapids, water falls, or land separating rivers from the lakes. Ask students to locate and discuss the roles of the Erie Canal, the Welland Canal (part of the St. Lawrence Seaway system), and the Soo Locks.

EXPLORE:

- Explain that students will do an activity that will show them the changes the Great Lakes have gone though in the past several hundred years that have impacted the fish in the lakes.

- Assign students to eight small groups, and give each group a time period card and a stack of note cards. Depending on the size of the group, some time periods can be combined to create fewer stations. Have students write out one timeline event on each note card

Supporting students during exploration: Questions that the teacher could ask to guide the exploration.

- Were these events positive or negative, or did they not have an impact on the health of the fishery?

- Did these events have to do with technology, the environment, social change, or a combination?

EXPLAIN:

- Have students develop a creative way to orally present their time period to the class, highlighting what they think are the most important events. They will have 3-5 minutes to present the events during the following class period. Every student should participate in the oral presentation. Have the students post their note cards in chronological order along a class timeline once they have planned their presentation.

- In the next class, students present their timeline sections to each other. Each presentation should include highlights from the time period, an explanation of which events seem most important to the Great Lakes fishery and a research question each student had after learning about this time period.

- After listening to each other’s presentations, look around the room at the changes that have been posted.

ELABORATE:

Supporting students during elaboration: Questions that the teacher could ask to clarify student thinking.

- How did we know there were problems in the Great Lakes fishery?

- Think about Lake Erie. Why did Lake Erie get singled out early on for its environmental problems? Think about the size of Lake Erie compared to the other lakes. It is much smaller. How does Lake Erie serve as a warning signal for the rest of the lakes?

- Which positive and negative changes seemed to have the biggest impact on the fishery? Students should discuss specific events. The changes were categorized as social, environmental and technological. Which kind of changes seemed to have larger impacts?

- Choose one of the research questions raised by the student groups (see #2 in the previous section). Discuss what observations or experiments could be done to answer the research question

Future Wheels: Have each student choose two changes that happened to the fishery:

- Write the change at the center of the page and draw lines toward words that answer the question: What did this change mean?

- Remember that changes and their results can be both positive and negative.

- As an example, choose one change and work through it on the board with the class.

- Example:

An increase in human population means: more fishing, more eating of fish, fewer fish, more fish sales, more shipping more invasive species

Another aspect of a growing human population could be: more farmers--more variety in food types--less fish being eaten

- Other ideas might include:

- Invasive species mean…

- Canals mean….

- War means…

- Overfishing means…

- People who care about the Great Lakes mean…

EVALUATE:

Supporting students during evaluation: Questions the teacher could ask to tie student ideas to big ideas.

New Vocabulary List new terms and definitions

Sources

Alliance for the Great Lakes. 2010. “Something’s Fishy.” Great Lakes in My World K-8. Chicago, IL.

Brandon C. Schroeder, Dan M. O'Keefe, and Shari L. Dann. 2019. Ann Arbor, MI: Michigan Sea Grant. The Life of the Lakes: A Guide to the Great Lakes Fishery, 136 pages.( https://www.amazon.com/Life-Lakes-4th-Ed-Fishery-ebook/dp/B07RHF1LJ5)

See also https://fishingbooker.com/blog/history-of-fishing-on-the-great-lakes-part-1/ and https://fishingbooker.com/blog/history-of-fishing-on-the-great-lakes-part-2/

- Ask students to write an answer for the following: How have humans both hurt and helped the Great Lakes? Give specific examples.

- Ask students also to write three to five questions that will require additional research on the Great Lakes fishery. Some aspect of the question and research must be related to impacts of past events on the Great Lakes fishery. These questions can be used for class research projects that result in experiments (hands-on activities), research papers, or educational posters.

Supporting students during evaluation: Questions the teacher could ask to tie student ideas to big ideas.

- What change(s) seems to have the most impact on Great Lakes fish?

- What caused the problems in the Great Lakes? Ultimately, human action.

- How did humans go about trying to solve the problems?

New Vocabulary List new terms and definitions

- Bioregion: a region whose limits are naturally defined by topographic and biological features (such as mountains, watersheds and other ecosystems)

- Commercial catch: fish that are taken out of the water by people to sell for use as food or other products

- Commercial fishing: capture of large quantities of fish using nets, trawlers and/or lines in order to sell to others as a food product

- Fishery: the activity or business of fishing; a place or establishment for catching fish. Currently, in the Great Lakes, the fishery is the common resource of naturally reproducing and stocked fish species that moves across state and federal boundaries and supports a large sport fishing industry and a much smaller commercial fishing industry

- Invasive species: plant or animal that is not native to an ecosystem and successfully competes against native species for food and shelter, causing harm to the environment, ecology, or humans.

- Sport fishing: the pursuit and capture of game fish for the purpose of enjoyment and relaxation; may or may not include eating the fish caught

Sources

Alliance for the Great Lakes. 2010. “Something’s Fishy.” Great Lakes in My World K-8. Chicago, IL.

Brandon C. Schroeder, Dan M. O'Keefe, and Shari L. Dann. 2019. Ann Arbor, MI: Michigan Sea Grant. The Life of the Lakes: A Guide to the Great Lakes Fishery, 136 pages.( https://www.amazon.com/Life-Lakes-4th-Ed-Fishery-ebook/dp/B07RHF1LJ5)

See also https://fishingbooker.com/blog/history-of-fishing-on-the-great-lakes-part-1/ and https://fishingbooker.com/blog/history-of-fishing-on-the-great-lakes-part-2/

New lesson plan ideas are welcome and will be uploaded as they are received and approved.

We especially encourage lesson plans about:

Invasive species,

Science and science careers

For information about submitting new lesson plans, please contact jchadde(at)mtu.edu

Lesson plan ideas from other web sites:

From Pennsylvania Sea Grant: 10 lesson plans about interactions of invasive species, biodiversity, and climate change

Creation of the above page of educational resources was funded in part by the Michigan Invasive Species Grant Program through the Departments of Natural Resources, Environmental Quality, and Agricultural and Rural Development.

This material is also based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1614187.

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

We especially encourage lesson plans about:

Invasive species,

Science and science careers

For information about submitting new lesson plans, please contact jchadde(at)mtu.edu

Lesson plan ideas from other web sites:

From Pennsylvania Sea Grant: 10 lesson plans about interactions of invasive species, biodiversity, and climate change

Creation of the above page of educational resources was funded in part by the Michigan Invasive Species Grant Program through the Departments of Natural Resources, Environmental Quality, and Agricultural and Rural Development.

This material is also based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1614187.

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.